In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more.

Welcome to the tenth post in the series, featuring a look at Forerunner by Andre Norton.

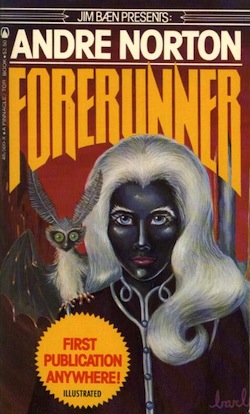

Just looking at the cover art to Andre Norton’s Forerunner will start you thinking about Dungeons and Dragons, as the pitch black skin and pale white hair of the elfin figure immediately makes your thoughts go to the dark elves, the drow. Here are two things that I’m into: spiders and elves. That ought to give you an idea of where I fall on drow; at least, once you get past the tired clichés. The first thing I did, then, upon seeing the cover for this, was flip to the copyright page—1981—and then look up the drow on Wikipedia. The drow’s first official mention is in the AD&D Monster Manual, 1977, with their first appearance in Hall of the Fire Giant King (G3) in 1978, which really nailed down their signature “look.”

Just an odd coincidence? Perhaps not, since Norton definitely was affiliated with Gary Gygax and Dungeons and Dragons. She wrote Quag Keep in 1979, the first official D&D tie-in novel, about a group of people from the “real world.” How did she know so much about the hobby? Well, because she played in Gary Gygax’s Greyhawk game in 1976, of course. Which means…well, what does it mean? I guess it probably means that either Norton thought Gygax’s dark elves looked cool, and cribbed it, or that they put their heads together and cooked that look up together, and that Norton repurposed it for Forerunner. An ancient race of ur-aliens, a pre-human proto-culture that explored the stars before the human species left their home world for the first time? Yes please!

Of the books we’re read, this is the one that most resembles the campaign I actually run. Jack Vance’s Dying Earth is at the root here, but Vance’s world is much more “high fantasy” than my usual game. What we get from Norton, however, something altogether more…granular. I don’t want to say “gritty,” since that brings up bad feelings of “extreme!” antiheroes with lots of pouches or a casual and cavalier attitude about life and death. The “science fantasy” of Forerunner doesn’t have the same feel as the surreal and madcap twists and turns of Vance. Rather, Norton presents us with a plausible world, a city with webs (drow pun unintentional) of guild politics and economic classes so rigid it might as well be a caste system. She delivers us a low magic setting, with one essential twist; one of the reasons the city exists and is prosperous is because of the spaceship landing grid just outside of town.

The fusion of elements is at the root of the story, and ultimately at the root of the main character. The lower tech level of the city of Kuxortal is where Simsa is from; she is a street urchin with some levels of thief who makes her living digging in the forgotten depths of the city for ancient archeological treasures. She meets Thom Chan-li Yun, a star-traveller, a man from another world who has been genetically engineered to, among other things, resist radiation sickness. Together, low and high tech, they explore ruins from the past. From before X-Arth, even—by the way, a great way to refer to the semi-mythological birthplace of humanity— a series of crumbling towers that themselves are built around an even more venerable secret. There is a whole series of these Forerunner books (and another Tor.com reviewer suggests that these elements are consistent across Norton’s work), and I’ve got to say, my interest is piqued!

DnD-isms? There are plenty. The flying cats, for instance; Simsa’s pet flying cat Zass is a good example of a familiar, and the “broken wing that is mended by magic later in the story”—oops, spoilers—is a clever device for a Dungeon Master who has a player that really wants an imp or pseudodragon at first level. I’ll keep that in my back pocket. So too are her “magic” ring and “magic” bracelet a good example of using the logic of Chekhov’s Gun for magic items; you can give out a ring and not reveal the magical properties until later. Note that “magic” is in quotes; there are “magic items” in the form of anti-gravity devices, gas grenades, and laser pistols—high tech items from the stars. But there is also a deeper, older “technology,” the Forerunner sciences, which adhere pretty tightly to Clarke’s Third Law. And to a deconstructed view of Dungeons and Dragon’s Positive and Negative energies, for that matter.

All in all I’m really impressed; this is my favorite new book I’ve encountered so far in the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons series, I think, because it exposed me to Andre Norton. She sure can write, and she does an excellent job with both the story in front of the reader—like the guild lords of Koxortal and the tribes within and without the city—as well as the parts of the story that go off into the “here there be dragons” nooks and crannies. The mentions of a race of librarian aliens, or little linguistic flourishes like “gentlehomo”—there are worlds within worlds, layers of historical occupation, layers of prehistoric occupation. It creates a textured tapestry, the verisimilitude makes me think that if I followed any strand of the narrative out into the broader context of the setting, I would find a whole new story behind that. You know what? I think I’ll have to read more to find out if that’s true.

Mordicai Knode can’t help but see the name “Norton” and think about Emperor Norton. That is just the way he’s wired. He and Tim Callahan have been delving the dungeons of DMs past for Advanced Readings in D&D for a while now. You can find Mordicai on Twitter or Tumblr.

Not to mention, drow in space are a total thing; Dungeon #92 had “Shadow of the Spider Moon”!

1. mordicai Drow in space pre-dates Dungeon #92; they were in the original Spelljammer setting.

The Forerunner’s go back a tad further:

Storm Over Warlock (1960), Ordeal in Otherwhere (1964), Forerunner Foray (1973).

She definitely could write and wrote a lot. There are many marvelous volumes that could await you. The “Zero Stone” books were my favorite. They are more strongly SF in nature but do also have some of those themes you mention. Forgotten aliens and interesting “pets”.

I loved a lot of Andre Norton’s early SF when I was a kid. Free traders, Forerunners, all of it, so long as there was even a faint veneer of SF. You can see this grand descent of Forerunner-synonym elder races appearing in galaxy-scale SF after that… all with their mysterious artifacts and ancient sites and resurrected legacies….

I have to say I don’t really see much direct D&D influence, though, not like Jack Vance’s Dying Earth magic system, ioun stones, and all that. Flying cats, meh: if that’s D&D then pretty much so is all adventure, fantasy, and romance fiction throughout history…. Of course the beauty of RPGs is anything *can* be a RPG setting. But come on, the relation of Forerunner to anything in D&D is very thin. It is after all possible to like someone else’s stuff without using it in your own work.

2. Tim_Eagon

Yeah, but they didn’t have their own ships or anything, did they? Or did I just never encounter them as a PC? I never ran the setting, sadly, though I have had the luck to play in it!

3. stevenhalter

But is this the first time we see them? Or were they always sort of…”drow-y”?

4. Miramon

I dunno, she is pretty spot-on for the look of the drow; knowing what a close relationship she had with the hobby, I find it hard to believe that is accidental. You are right that there isn’t as many straight lines, like Vance’s Excellent Prismatic Spray or such, but I think that Expedition to Barrier Peak is right in the same vein as this.

This is maybe the first book in this review series that has actually made me want to hunt it down and read it myself.

Mordicai@5:A lot of the time the Forerunners are just mentioned. There are actually multiple alien species with that title as I recall. Basically, a lost Galactic set of species with various powers/technologies/abilities.

I don’t recall at all if this is the first time with the ones that look like Drow.

I would guess, though, that Gygax was influenced by other earlier works such as the Witch World books and others.

7. fordmadoxfraud

It shouldn’t be too hard; Tor republished it recently. I will note, though, the bias in that, since a lot of the good stuff is already stuff you’ve probably read, your Conans & Vances.

8. stevenhalter

Witch World sounds very “Blue Star,” which is coming up later in this series…

I remember reading Forerunner Foray many, many years ago (probably before Forerunner came out) — now I’m also thinking I should go back and revisit the series.

I did not know that she had actually gamed with Gygax & co., although given Quag Keep I suppose that shouldn’t have been a surprise.

I’m going to have to look this book up. I read a lot of Norton when I was young, and remember lots of mention of the Forerunners, but in the stories I read, they were always in the background, not shown.

This book came out after I left for college, and I do remember that I stopped reading Norton at about that point, mistakenly thinking of her as a juvenile writer. Since then, I have come to my senses, and have caught up reading more of her work.

How she connects to D&D, I don’t know–the reason I comment so much on this reread series is not because I know a darn thing about D&D, I just find that Mr. Gygax and I read a lot of the same books when we were younger!

Forerunner was a term used in Norton’s Science Fiction for any pre-history advanced race. I don’t recall if any of Norton’s previous Forerunners were like Sisma.

“Forerunner Foray” is not directly related to this book or its sequel “Forerunner: Second Venture.” Norton would sometimes run across something she thought was cool and write a book about it. Forerunner Foray is one of those. It’s dedicated to psychic readings and how they might change archeology, forensics, and such. ESP figured into a lot of Norton’s science fiction.

The Thieves Guild figures into a lot of Norton’s science fiction–a lot of which predates D&D.

Norton was one of my favorite authors growing up. I like her science fiction and juvenile fantasy, but didn’t really care for her Witch World books (most of her adult fantasy). “Zero Stone” and its sequel “Uncharted Stars” were my favorites.

I loved Andre Norton when I was growing up. The Crystal Griffon was my favorite, but she wrote a lot of good stuff. Nice to see you review one of her books.

When I think of flying cats, I think of Corum and Jhary a Conel.

5. mordicai

I don’t have a lot of Spelljammer supplements and the original box set’s Lorebook of the Void said drow elves didn’t venture into space, but they eventually showed up. They had ships that looked like arachnids and often fought the neogi.

I’m not sure I’ve read this book by Norton. Now I’ll have to check the catalog when I get to work tomorrow.

So far, I have read Star Man’s Son from Norton, which was a great post-apocalyptic novel with a fantasy vibe.

11. hoopmanjh

Yeah, Forerunner, confusingly, is not the first of the Forerunner books!

12. AlanBrown

A thing I find really interesting is…historical positioning, I guess? When I read a Pathfinder book, for instance, I find a lot of overlap with the things those writers are cribbing from & the stuff I’m cribbing from in my game– notably, the planetary stuff borrows from a lot of the same sources, from John Carter to Hyperion.

13. goodben

Yeah, the “magic” in this book is definitely an overlap of super science & psychic powers.

14. percysowner

I wish I’d read more of her, but on the flip side, now I have more of her to read, as an adult!

15. Walker

Still haven’t read Corum, just Elric & Hawkmoon.

16. Tim_Eagon

Man, this is making me want to go on Ebay & get all of the old Spelljammer stuff, tout suite.

17. RobinM

&

18. Hedgehog Dan

I guess I should start thinking of what Norton to read next!

@19: I haven’t read a great proportion of Norton’s output (she was, after all, a very prolific author) but there’s a good deal of free Norton online. Baen have the omnibus editions Star Soldiers and Time Traders, while Project Gutenberg offers the following: “People of the Crater”, “All Cats Are Gray”, “The Gifts of Asti”, The Time Traders, The Defiant Agents, Key Out of Time, Plague Ship, Voodoo Planet, Star Born, Star Hunter, several historical novels and the first Forerunner book, Storm Over Warlock.

20. SchuylerH

I gotta say, I’d much rather pay for content than deal with the hassles of getting it free. Partly that is because I prefer print as a format (personally, not ideologically).

@21: Since you prefer print, I will recommend Baen’s long-running series of omnibus editions, many of which include books from the Forerunner universe. Maybe it’s just me but I note that your description of Forerunner made it sound somewhat similar to Mary Gentle’s Golden Witchbreed.

Andre Norton was one of my favorite writers and well worth a reread. Her Witch World series is one of the classics of the field as well as the time traders. A large number of her stories involve finding an ancient civilization, with greater magic/science and exploring the ruins, I think in many ways a possible inspiration for many a dungeon crawl.

I would note that Quag’s Keep is another of the ‘modern day people’ thrown into a fantasy world’ books, although that one was very notable because you could see the dice rolling (literally, in the original sense of ‘literally’, the characters had wristbands of dice attached to their arms that rolled when they did actions). It was intereresting, but very different.

I did not know that Andre was that associated with D&D, that is neat to find out. She had enormous influence on the SF field in general.

22. SchuylerH

Man, one of the best-worst things about this reading series is that my long pile of “to-read” books just keeps getting bigger.

23. JonLundy

WAIT. Wristbands with dice, WHAT.

I grew up reading Andre Norton, and have recently read the Baen Book omnibus e-book editions of a lot of her work. When I was 8 or 9 I “borrowed” 2250 A.D. (also known as Star Man’s Son) from a cousin because it showed a man on a wooden raft with a puma-sized cat with Siamese markings. I still have it.

A lot of her books were in the same future history universe. Another good one (besides 2250 AD) is Catseye. It’s about a refugee who ends up exploring an alien city, with telepathic animals for companions. Fun stuff and still holds up very well compared to current science fiction. Her Star Trader books are great fun too.

25. nimdok

This makes me super excited. I am getting ready to be an Andre Norton fan!

Norton’s vast catalog is one of those childhood joys that I am getting so much more from now, as an adult reader. Her books are not big, but they are vivid and strong. My love of space opera and sword&planet fantasy comes more from her than Star Wars, I suspect – I was reading Norton long before 1977.

27. Crane Hana

Have you ever read Anne McCaffery’s Planet Pirates? You might dig it.

Just this summer I shipped a box to my sister containing nearly every book Andre Norton wrote. Bigger than a “banker’s box” of books! She did run themes through several series, and her Forerunner concept was good. I didn’t know of her connection to Gygax either!

29. Ed Barnard

I’ve learned a LOT while doing this reading series.

Since I was last here, I have read another several dozen or so of Norton’s books and, as such, I am now convinced that Norton’s adventures were, in the early days of D&D (at least) the best source material for a homebrew campaign:

Down-on-their-luck protagonist desperate enough (or forced by the circumstances) to go on a foolhardy adventure? Check.

Human, alien and/or animal companions joining the party? Check.

Supporting characters who are never quite what they seem? Check.

Tech and psychic abilities that the DM can easily convert to Gygaxian magic? Check.

Well-described setting for the heroes to explore? Check.

Perilous encounters with weird creatures? Check.

Ruined cities or enemy bases full of loot and danger for the party to crawl through? Check.

Dark and terrible things lurking in the black depths? Check.

Hints and glimpses of long-vanished civilizations? Check.

An author so profilic that you will practically never run out of source material? Check.

I too have read more Nortons since I was last on this thread. Fifty of them.